Very, VERY, slowly. No, slower than that. Glacially*. There are laces out there that a skilled worker could labor at all day and be ecstatic to make just an inch or two of progress, if they were dexterous enough. Most modern laces are a little faster than that, but progress is still measured in inches per day, especially for complex designs.

Each of those bobbins heaped around her pillow controls a separate thread in the design and makes its own path through the lace.

When it comes to what people think of as lace, there are two main forms - needle lace and bobbin lace - and a whole host of other, still technically laces like tatting, crocheted and knitted laces, fine macrame, woven laces, etc. I’ll go into needle and bobbin laces here, since those are mainly what drove the lace craze in Europe.

Needle lace, as one can expect, is made with a needle. It can be made on a background fabric that is cut away, as in the Norwegian hardanger:

In this case the edges of the fabric are stabilized by stitches, and then threads of the fabric are cut away (very carefully) and the remaining net is stabilized and decorated by yet more stitching. It is lace, but a bit sturdier and more hard-wearing than what you may be thinking of. There are less geometrical forms of lace formed by cutting away parts of the ground fabric, and these are loosely clumped under the label Cutwork. Reticella, broderie anglaise, and carrickmacross are all embroidered laces. Most pieces are done in white, though it’s not a requirement.

These count more as embroidery than lace, but they are an important stepping stone to see how lace came about. The drive for ever finer and more delicate designs led to more and more of the fabric being cut or drawn away. What if you didn’t need fabric at all?

The Italian punto in aria (literally ‘stitches in the air’) is often considered the first true needle lace because it didn’t need to be stitched onto a woven fabric at all. The laces of Burano are some of the finest laces in the world, and they’re still made the same way they always were - by hand, with a needle, using a parchment pattern.

from DreamDiscoverItalia

Bobbin laces are nearly as old as needle laces, and evolved independently about the same time. They have more in common with weaving and braiding than needle lace, but since the finished product is similar they’re often grouped together.Bobbin lace can be made comparatively faster, since you work with several (usually four) threads at once. These laces are formed by plaiting and twisting threads on a pillow, and using pins to hold the twists until the piece is together enough to be released. They can be formed as long narrow ribbons called tape lace (common for edgings on garments) like this torchon lace:

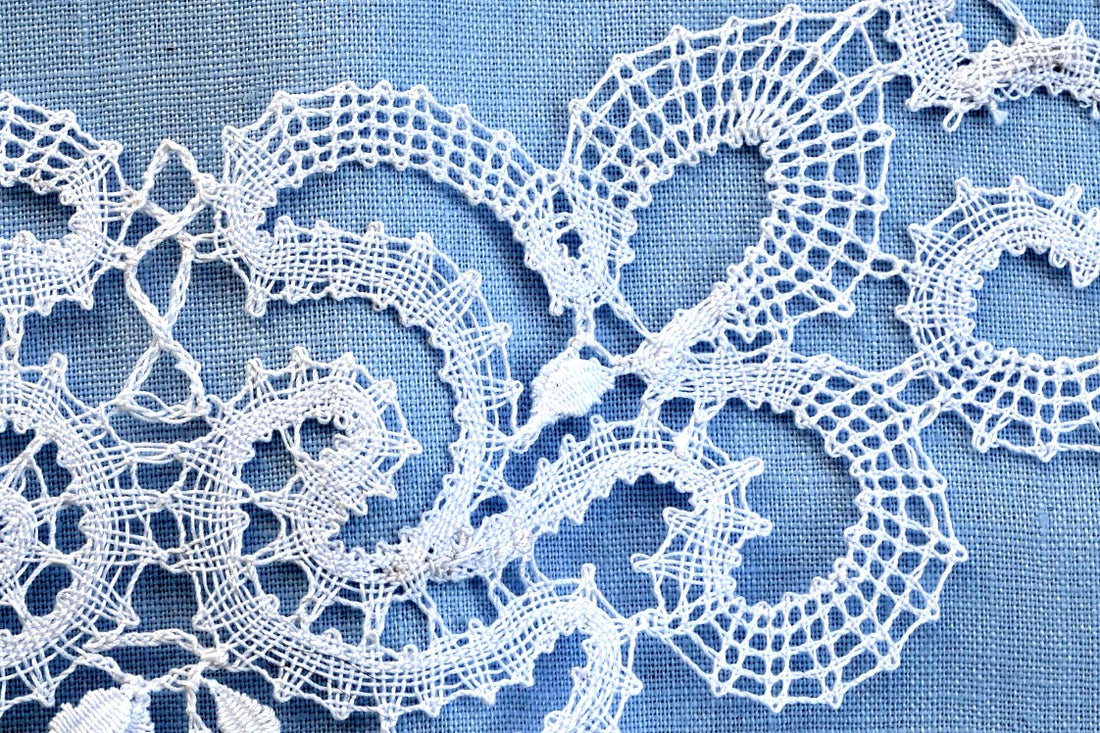

or in free-form pieces, used either singly or as motifs to be connected together, like this vologda lace that I wore as a necklace on my wedding day:

This is in fact three separate pieces, connected by ‘sewings’ - looping a thread of one area through a corresponding loop of another area to attach them. If you look closely you can see the two small wing shaped pieces on the edge of the design are only nominally attached to the larger central motif - those connections are the sewings.

Bobbin lace and needle lace may be used together in the same piece, complicating matters for those who would try to puzzle out an item’s provenance. In some of the large lacemaking workshops girls would churn out an assortment of needle lace sprigs, sprays, and motifs, to be set into a bobbin lace ground - a good way to get the infinite customization of needle lace but with a little additional speed of bobbin lace for the large open areas.

Setting motifs into a ground was a bit more difficult than just making the motifs, and the lace cutter - the one who would inspect the work and make alterations and repairs when necessary - took even more skill. (Can you imagine cutting into someone’s days or weeks of labor, perhaps with them right there?) The real rock star of the studio was the pattern drafter - it takes a special kind of mind to create lace patterns, and ‘prickings’ as they’re called, were traded or jealously guarded according to the temperment of the individual and the political climate.

Lace was small, portable, and very, very expensive - a favorite for smugglers and an easy way to transport a large store of wealth. The lace middlemen profited the most off of this lucrative trade, but even a lowly lacemaker with just a few patterns would make more with lace than she could working as a laborer. Still, it wasn’t the best of jobs - four girls (or sometimes sixteen) would be clustered around the light of a single candle in the winter with their pillows and bobbins. Open fires would dirty the work, so small personal heaters filled with live coals might be placed under their skirts (a fire hazard, to be sure) or the lacemakers might work over a barn so the heat of the animals kept them from freezing. Summertime was much nicer, when so much sunlight made lacemaking easier on the eyes. Many old lacemaking songs are about finishing one’s work before the candles were lit, since weak candlelight made things so much harder.

The incredible labor cost of lace led to it being mechanized sooner than the sewing machine - stocking frames were first adapted to make a sort of lace in 1800, and bobbinet machines - invented by John Heathcoat after watching a lacemaker at work - in 1808 (The first sewing machine was invented in 1834 or 1846, depending on how you define it). This bobbinet made a fine regular ground nearly on par with what the local girls could produce, and it wasn’t long until refinements in the design led to patterned laces being made by the yard as well. That was the beginning of the end for handmade lace, but it held on commercially until WWI in Italy. Small amounts are still produced, but it’s not easy to find examples of this dying art, and harder to find those that can still make them.

Although lace is not made for sale at the scale that it was, there are still some who practice this beautiful art, especially in the communities well known for it in the past. Fortunately the internet allows lacemakers to connect with each other, order supplies, learn, and share their work even if there is no tradition of lace in their immediate neighborhood.

At Broiderie Stitch, we produce a small amount of bobbin lace, and we’ll hopefully be adding more patterns later this summer. Researching and deconstructing old patterns to preserve them for the future is an important part of what we do, and you can see more of our work here.

*Lacemaking is actually significantly slower than a glacier, which can reach 150 feet a day, according to the University of Washington.

4 comments

Hi Cornelia!

It’s so good to hear from someone who was able to learn from others and in a place where bobbin lace is much more well known. Where we are in the U.S, lacemakers are very few and far between. I am so grateful to the many authors who have written about lace; without their instructions and knowledge, I would never have learned this craft.

Warmly,

Jackie

U.S.A.

Hallo,

Ende der 80er Jahre habe ich in der ehemaligen DDR den Beruf als Handklöppler erlernt. Mit der Wende Anfang 90er ging dieser damals Kunsthandwerkberuf leider kaputt. Das heißt, es wurde nicht mehr das bezahlt, was diese Spitze wert ist. Außerdem kamen die Spitzen (-Deckchen u.a.) außer Mode. Davon abgesehen wird hier in ganz Deutschland und auch ganz Europa (Ost und West) immernoch recht viel geklöppelt. Hier in meiner Heimatregion Erzgebirge gibt es in fast jedem Ort Klöppelgruppen und die Volkshochschule und andere Schulen biete Klöppelkurse an. Im September gibt es in Annaberg die sogenannten “Klöppeltage” im Erzhammer, wo sich Klöppler:innen nicht nur aus Europa treffen. Ich kann empfehlen, beim Deutschen Klöppelverband e.V. oder auch beim Erzgebirg-Sächsichen Klöppelverband e.V. im Internet mal reinzuschauen. Auch bei Facebook sind einige Gruppen (nicht nur deutsche) vertreten.

Ich könnte noch viele Zeilen schreiben, denn es gibt viel über Spitzenherstellung zu erzählen und es gibt auch sehr viele Bücher dazu. Sogar einen extra Verlag.

Herzliche Grüße und viel Spaß beim Klöppeln

Cornelia Ring

Deutschland

Hi Mariëlle,

Thanks for your comment! It’s always nice to hear from another lacemaker. :) What styles do you like to make the most?

Though modernization means we’ll probably never see lace made on the scale that it was, the internet has been an incredible way for lacemakers to connect with each other and share work and ideas – not to mention ordering supplies, even if the modern threads aren’t as fine as some of the historic ones. With new lacemakers like you picking up their bobbins, the art can never truly die.

Warmest regards,

Jackie

U.S.A.

Hello,

Good work, studying lace history. Is lace making dying? As a way to earn one’s daily bread, yes, but in U.S. and in Europe there are quite some people who make bobbin lace as a hobby. Some make modern work, some make old patterns. On Facebook you can find groups of people who do this. I am one of them although I am still learning.

Hoping lace making will never die,

With cordial greetings,

Mariëlle ten Berg

The Netherlands